Tandragee

| Tandragee | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

The Square, Tandragee (2009) | |

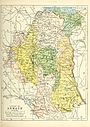

Location within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 3,545 (2021 Census) |

| Irish grid reference | J030462 |

| • Belfast | 25 mi (40 km) |

| District | |

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CRAIGAVON |

| Postcode district | BT62 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | |

| NI Assembly | |

Tandragee (from Irish Tóin re Gaoith, meaning 'backside to the wind')[2] is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It is built on a hillside overlooking the Cusher River, in the civil parish of Ballymore and the historic barony of Orior Lower.[3]

Earlier spellings of the name include Tanderagee and Tonregee.[2] It had a population of 3,545 people in the 2021 census.[4]

History

[edit]Overlooking the town is Tandragee Castle. Originally the seat of the Chief of the Name of the O'Hanlon Irish clan and Lord of Orior, the castle and surrounding countryside were confiscated and granted to Oliver St John and his heirs during the Tudor conquest of Ireland and the Plantation of Ulster.

According to D. J. O'Donoghue's account of his 1825 Irish tour, Sir Walter Scott was fascinated by the life and career of Redmond O'Hanlon, a local Rapparee leader. Hoping to make him the protagonist of an adventure novel, Scott corresponded with Lady Olivia Sparrow, an Anglo-Irish landowner whose estates included Tandragee. Although Scott asked Lady Olivia to obtain as much information as possible about O'Hanlon, he was forced to give up on the project after finding documentation too scanty.[5]

Tandragee Castle was rebuilt in about 1837, after having previously been destroyed during the Irish Rebellion of 1641, for George Montagu, 6th Duke of Manchester. Its grounds have been home to the Tayto potato-crisp factory since 1956, after being bought by businessman Thomas Hutchinson.

Ballymore Parish Church is located beside Tandragee Castle and has a history spanning over 650 years, connected to the Dukes of Manchester until the mid-1950s. The church was mentioned in 14th-century records but it was burnt down by Edmond O'Hanlon in the Irish Rebellion of 1641.[6] It was reconstructed in 1812 as it had become inadequate for the congregation's needs. During construction, remnants of the old walls were found, showing signs of fire damage from the Irish Rebellion of 1641.[7]

The Troubles

[edit]In 2000, Tandragee was scene of the Murders of Andrew Robb and David McIlwaine, two teenaged local Protestants who were unaffiliated with any paramilitary organization, by three members of the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade and as part of an ongoing Loyalist feud between the UVF and LVF.[8]

World War II

[edit]On May 25, 1942, the peaceful rural landscape surrounding Tandragee was disrupted when Supermarine Spitfire BL325 crashed near Cordraine Orange Hall. The aircraft was involved in a coordinated training exercise alongside ground forces. During a low-altitude flight, the pilot clipped a tree, resulting in the plane landing upside down in a field.[9]

Just over a year later, life in the town would experience a significant transformation with the arrival of American GIs from the 6th Cavalry.[10] In 1943, Alexander Montagu, the 10th Duke of Manchester, leased Tandragee Castle to the United States Army for use during World War II.[11]

Tandragee's links to the primary Belfast-Dublin railway, along with its proximity to the River Cusher and Newry Canal, positioned it as a strategic staging area for the United States Army in 1943.[12] Tandragee railway station experienced the arrival of thousands of soldiers during World War II.[13]

A significant event in the history of the 6th Cavalry occurred in the town when the unit conducted its final parade on December 31, 1943, in Tandragee. Following this, the regiment transitioned to become the 6th Mechanized Cavalry Group, which was comprised of the 6th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron and the 28th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron.[12]

Reports suggest that General George S. Patton was a visitor to Tandragee Castle in 1943. While inspecting troops in Northern Ireland, he was guest of honour at a dance in the castle.[11]

The war memorial in Tandragee stands at nearly 25 feet, overlooking the town at The Square adjacent to the castle gates, commemorating the names of soldiers who served in both World War I and World War II.[14]

Tandragee Volunteers

[edit]In the late 18th century, Britain was engaged in the American Revolutionary War. This situation heightened the risk of invasion by French and Spanish forces, especially in Ireland. In response, private groups of Volunteers were formed throughout Ireland and were equipped and managed independently, predominantly consisting of Protestants, mainly from the Church of Ireland. A number of these Irish Volunteers originated from Ulster, with several companies established in the Tandragee region.[15]

The Tandragee Volunteers, organised by Captain Nicholas Johnston, were fitted with scarlet uniforms faced with white details. Johnston established another company in Tandragee known as the Tandragee Invincibles. In the churchyard, there is a grave dedicated to one of its volunteers, John Whitten, who died in 1785.[15]

Additional companies included the Tandragee Light Dragoons, led by James Craig. Volunteer activities primarily served a ceremonial purpose, featuring reviews and shooting competitions. The Tandragee Volunteers played a notable role at Lisnagade in 1791, when a significant faction conflict occured. A group known as the Defenders established themselves at Fort Lisnagade with the intent to confront a group of Peep O' Day Boys who were commemorating King William's triumph at the Battle of the Boyne. This inspired the creation of a ballad known as Lisnagade ("Ye Protestants of Ulster").[16]

The Ulster Volunteers established the first and only all-Ireland Parliament, but their influence declined after the American Revolutionary War as new government-sanctioned groups emerged, such as the Yeomanry. Following the Battle of the Diamond, the Yeomanry became a predominantly Orange force. Established in 1796, the Tandragee Yeomanry, along with the County Armagh Yeomanry, played a key role in suppressing the 1798 United Irishmen Rebellion. With the Irish Volunteers disbanded and the United Irishmen defeated, the Acts of Union 1800 dissolved the all-Ireland Parliament.[15]

Home Rule crisis

[edit]From the introduction of the First Home Rule Bill, Tandragee strongly opposed the idea and played a significant role in the establishment of a proposed 'Orange Army' in 1886. Tandragee also had a strong representation in the Ulster Defence Union. In the central assembly of 600 members appointed on October 21, 1886, the southern region, including Armagh, Cavan, and Monaghan, was represented by eight local representatives: Rev. P.A. Kelly, Rev. W. McEndoo, Rev. R.J. Whan, Maynard Sinton, Thomas White, William O’Brien, John Atkinson, and Rev. George Laverty.[15]

The Unionist Club movement, which initially emerged in 1893 to resist the Second Home Rule Bill, had seen a decline over the years but experienced a resurgence in 1910. Branches were swiftly established in Tandragee, Clare, Scarva, Poyntzpass, and Ballyshiel. In September, under the supervision of the 9th Duke of Manchester, members of the Tandragee Club engaged in drills prior to the Ulster Covenant.[15]

After the Ulster Covenant, the Unionist leadership opted to unite the various organisations involved in drilling efforts. By December 1912, the County Armagh Committee included several notable figures from the business sector, the legal field, and the local aristocracy. The representatives from Tandragee were Rev. R.J. Whan and George Davison. These individuals played a crucial role in the eventual formation of a local Battalion of the Ulster Volunteer Force.[15]

The emergence of the Third Home Rule Crisis saw Tandragee identified by the RIC as early as 1912 as one of only ten locations where military drills were occurring. When the Ulster Volunteer Force was formed, the community welcomed it with enthusiasm. The population of the Tandragee area ultimately became the majority of what would later develop into an eight-company strong Third Battalion of the County Armagh Regiment U.V.F. - also known as the Tandragee Volunteers.[17] Tandragee Castle served as the headquarters for the Tandragee Volunteers, with records indicating that the 9th Duke of Manchester occasionally inspected the troops and permitted the use of his estate.[15]

On August 4, 1914, the UK entered WWI, prompting thousands of Ulster Volunteers to join the British Army. Some were returning officers, while others, including former soldiers, felt compelled to fight against the 'Hun.' A public initiative soon formed to integrate the Ulster Volunteer Force into Kitchener's new Army, with hundreds enlisting from the Tandragee District, with a significant number joining the Armagh Volunteer Battalion of the 9th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers.

A remembrance mural honoring the Third Battalion of the County Armagh Regiment U.V.F. and 9th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers is located at the junction of Montague Street and Ballymore Road in Tandragee.[18]

Orange Order district

[edit]

Tandragee District No.4 is one of 11 Orange Districts within County Armagh, comprising 21 private lodges and nearly 650 members. Every year on The Twelfth (12 July), the lodges within the district participate in the "Ring Ceremony" at the square, which includes a brief religious service. Tandragee is the only district to hold such an event.[19]

Tandragee District No.4 hosts The Twelfth every 11 years, as part of a rotation in which each district lodge in County Armagh takes its turn to organise the event.[20]

The district has its origins in 1796, the year following the establishment of the Orange Order. By 1834, the district was home to 27 lodges with a total of 810 members. In 1900, this number had decreased to 25 lodges with 750 members, while as of the early 21st century, there are 21 lodges with over 700 members.[21] The inaugural Orange parades in Tandragee occurred on 12 July 1796, coinciding with the first Twelfth demonstration held at Lurgan Park. At that time, the district comprised 14 lodges.[21]

Tandragee District Hall was constructed in 1912 and initially established as a Protestant Temperance Hall. The building later functioned as a picture house during the 1940s and for later for dances, until it eventually transitioned to function as Tandragee District Hall.[22] The hall also holds other events throughout the year.[23]

On New Year's Day 2008, the hall was the target of an arson attack, during which the door was forcibly opened, the interior was ignited and the hall sustained significant smoke damage.[24][25]

Education

[edit]Schools in the area include:

- Tandragee Primary School[26]

- Tandragee Junior High School[27]

- Tandragee Nursery[28]

- Button Moon Play Group[29]

Sport

[edit]Motorcycling

[edit]The largest event to occur in the town is when it plays host to the Tandragee 100 Motorcycle Races.[30] First held in 1958 as a 100 mile handicap race, the Tandragee 100 has played host to a wide-range of road racers notably: Guy Martin, Joey Dunlop, Ryan Farquhar and Michael Dunlop.[30] The race did not take place during 2020 or 2021 due to COVID-19, was cancelled in 2023 due to insurance costs and again in 2024 due to lack of course resurfacing.[31]

Other sports

[edit]Tandragee Rovers play in the Mid-Ulster Football League. There is a golf course within the grounds of Tandragee Castle. It is 5,589 metres, par 71, and a hilly parkland course.[citation needed]

Industry and transport

[edit]

Thomas Sinton opened a mill in town in the 1880s, an expansion of his firm from its original premises at nearby Laurelvale – a model village which he built. Sintons' Mill, at the banks of the Cusher River, remained in production until the 1990s.[32] The potato-crisp company Tayto has a factory and offices beside Tandragee Castle. It offers guided tours.

Tanderagee railway station opened on 6 January 1852 and was shut on 4 January 1965.[33]

Northern Ireland Electricity has an interconnector to County Louth in the Republic of Ireland from the outskirts of the town.[34]

Demography

[edit]2021 census

[edit]Tandragee had a population of 3,545 people in the 2021 census.[4] Of these:

- 76.92% were from a Protestant background and 10.75% were from a Roman Catholic background[35]

2011 census

[edit]Tandragee had a population of 3,486 people (1,382 households) in 2011. Of these:[36]

- 23.26% were under 16 years old and 12.62% were aged 65 and above.

- 50.06% of the population were male and 49.94% were female.

- 81.84% were from a Protestant background and 11.70% were from a Roman Catholic background

2001 census

[edit]For the 2001 census, Tandragee was classified as an intermediate settlement by the NI Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) (i.e. with population between 2,050 and 4,500 people). On census day (29 April 2001), there were 3,050 people living in Tandragee. Of these:

- 24.9% were aged under 16 years and 14.3% were aged 60 and over

- 48.0% of the population were male and 50.0% were female

- 86.9% were from a Protestant background and 10.5% were from a Roman Catholic background

- 2.0% of people aged 16–74 were unemployed.[37]

See also

[edit]- Tandragee Idol, an Iron Age stone figure

References

[edit]- ^ Tandragee Archived 29 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Placenames Database of Ireland.

- ^ a b Place Names NI

- ^ "Tandragee". IreAtlas Townlands Database. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ a b "2015 Settlement". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ D. J. O'Donoghue, Sir Walter Scott's Tour in Ireland in 1825: Now First Fully Described, Dublin: O’Donoghue & Gill, 1905. Pages 10–11.

- ^ "1641 CLRLE | Deposition of Elizabeth Rolleston". 1641dep.abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "History". www.ballymore.armagh.anglican.org. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "BBC News | NORTHERN IRELAND | Murder victims 'had no terror links'". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Spitfire BL325 crash near Tandragee, Co. Armagh". WartimeNI. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "List of WW2 U.S. Army units in Northern Ireland ( listed by location ) part 1of4". www.belfastforum.co.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Tandragee Castle, Tandragee, Co. Armagh". WartimeNI. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Tandragee, Co. Armagh during the Second World War". WartimeNI. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Madden Bridge Railway Station, Tandragee, Co. Armagh". WartimeNI. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Tandragee". www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Quincey. "Tandragee Ulster Volunteers". Bygonedays.net. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "Ye Protestants of Ulster / Lisnagade". www.musicanet.org. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ McKenna, Micheal (8 July 2019). "Tandragee history re-discovered". Armagh I. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Wall mural commemorating 9th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers". www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "Co Armagh Grand Orange Lodge detail 11 districts' Twelfth 'near home' plans". Armagh I. 1 July 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Tandragee Twelfth: All you need to know ahead of world's largest gathering of Orangemen". Armagh I. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Gearing up for a 'Glorious Twelfth' in Tandragee".

- ^ Clark, Henry (20 June 2009), English: Temperance Hall Tandragee As well as home to orange order L.O.L No4. It was as a picture house and later for dances, retrieved 12 October 2024[better source needed]

- ^ Hammond, Hazel. "County Armagh Grand Orange Lodge holds 2023 Mission". www.ulstergazette.co.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Orangemen defiant after latest arsons". The Irish Times. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Inside the tandragee orange hall hi-res stock photography and images". Alamy. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Home | Tandragee Primary School". www.tandrageeps.co.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Tandragee Junior High School TJHS, Co. Armagh, NI". Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Education Authority".

- ^ "Button Moon Pre-School (Tandragee) - Directory Listing". www.familysupportni.gov.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ a b "ABOUT - Tandragee". 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Tandragee 100: Irish national road race cancelled for 2024". BBC Sport. 18 December 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Tandragee to get mill back in action, The Belfast Telegraph

- ^ "Tandragee station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- ^ Eirgrid-SONI Transmission System Map, October 2007

- ^ "Religion or religion brought up in". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Census 2011 Population Statistics for Tandragee Settlement". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). Retrieved 7 June 2021.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. Crown copyright.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. Crown copyright.

- ^ NI Neighbourhood Information Service