Oscar Charleston

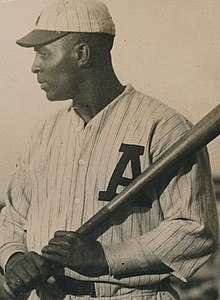

Oscar McKinley Charleston (October 14, 1896 – October 5, 1954) was an American center fielder and manager in Negro league baseball. Over his 43-year baseball career, Charleston played or managed with more than a dozen teams, including the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords, Negro league baseball's leading teams in the 1930s. He also played nine winter seasons in Cuba and in numerous exhibition games against white major leaguers. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976.

One of the Negro leagues' early stars,[10] Charleston was by 1920 generally considered "the greatest center fielder and one of the most reliable sluggers in black baseball."[11] He and Josh Gibson share the record for Negro league batting titles with three. He was the second player to win consecutive Triple Crowns in either batting or pitching (after Grover Cleveland Alexander), a feat matched just one time by a batter. He is now credited with having won the Triple Crown (leading in batting average, home runs, RBI) three times, which is the most for any player in Major League Baseball.[12] He holds the third-highest career batting average, behind Josh Gibson and Ty Cobb, and the fourth-highest career OPS.[13]

In 1915, after serving three years in the U.S. Army, the Indianapolis native continued his baseball career as a professional with the Indianapolis ABCs. He played in the Negro National League's inaugural doubleheader on May 20, 1920. His most productive season was with the Saint Louis Giants in 1921, when he hit 15 home runs, 12 triples, and 17 doubles, stole 31 bases, and had a .437 batting average. In 1933, Charleston played in the first Negro National League All-Star Game at Chicago's Comiskey Park and appeared in the League's 1934 and 1935 all-star games. In 1945, Charleston became manager of the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers and helped recruit black ballplayers such as Roy Campanella to join the first integrated Major League Baseball teams. His career ended in 1954 as a player-manager for the Indianapolis Clowns.

Early life and family

[edit]Oscar McKinley Charleston was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on October 14, 1896, the seventh of eleven children; his younger brother Bennie Charleston played alongside him on the 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords. Charleston's father, Tom Charleston, was a construction worker and a former jockey. Oscar spent his youth playing sandlot baseball and was a batboy for the Indianapolis ABCs.[14][15]

On March 7, 1912, fifteen-year-old Charleston lied about his age to enlist in the U.S. Army. He was assigned to Company B of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Regiment and served in the Philippines, where he ran track and played baseball on the regiment's team. In 1914 the seventeen-year-old, left-handed pitcher played a season representing the regiment in the Manila League. Charleston also pitched a 3–0 shutout and scored a run during a local all-star game. At the end of his tour of duty, Charleston decided not to reenlist. He returned to Indianapolis in April 1915.[16]

On November 24, 1922, Charleston married Jane Blalock Howard, a widow from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The couple often traveled together during the early years of their marriage when he was a player and manager for the Harrisburg Giants. The Charlestons had no children and separated during the 1930s, but they never divorced.[17]

Career and statistics

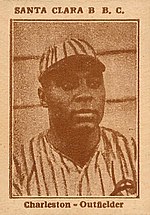

[edit]Between 1915 and 1954, Charleston was a player and/or manager for the Indianapolis ABCs, Lincoln Stars, Chicago American Giants, Detroit Stars, Saint Louis Giants, Harrisburg Giants, Hilldale Club, Homestead Grays, and Pittsburgh Crawfords, as well as the Toledo Crawfords, Indianapolis Crawfords, Philadelphia Stars, Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, and the Indianapolis Clowns.[2][3] Charleston was a player-manager until 1941, but his thirty-nine year baseball career continued as a team manager until his death in 1954.[18][19] In addition to his play in the Negro leagues, Charleston participated in numerous exhibition games against all-white teams in the years before major league baseball became integrated in 1947. He also played nine winter seasons in Cuba.[20]

Official statistics for the Negro league players are incomplete and vary among sources. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum's website and Baseball Reference's website reported as of March 6, 2018, that Charleston's career batting average over 239 Negro league games and twenty-six seasons (1915–1941) was .339, with a slugging percentage of .545. The Hall of Fame website also noted that Charleston had a .326 lifetime batting average in exhibition play against white major leaguers.[9][21][22] Data from other sources provided different statistics, but do not include specific periods of time. For example, the online version of Encyclopedia Britannica lists Charleston's lifetime overall batting average as .357,[15] as did baseball historian James A. Riley in his book The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (1994). Riley further stated that Charleston had a .326 batting average in exhibition games against white major league players and a .361 batting average in nine seasons of winter games in Cuba.[23]

Early years, 1915–1920

[edit]After his honorable discharge from the U.S. Army in 1915, Charleston returned to the United States and immediately began his baseball career with the Indianapolis ABCs. He was paid $50 per month.[24] On April 11, 1915, Charleston pitched his first game for the ABCs, a three-hit, 7–0 shutout in an exhibition game against the Reserves, a semiprofessional team of white players. Charleston, called "Charlie" by his teammates, soon moved to the center field position, where he became known for playing shallow (close behind second base) and his one-handed catches. Charleston was especially adept at catching high flies, using his running speed to retrieve balls above his head. His strong batting and fielding skills also earned Charleston the nickname of the "Hoosier Comet."[25]

In addition to his skills as a ballplayer, Charleston was known for his combative nature and willingness to fight when provoked. One memorable incident occurred during a game that the Indianapolis ABCs played against a team of white major and minor leaguers in Indianapolis on October 24, 1915. When ABCs player Elwood "Bingo" DeMoss got into a dispute with umpire James Scanlon over a bad call against the team, Charleston ran in from center field and punched the umpire, knocking him to the ground. According to local newspapers, the ballpark erupted into "a near race riot." Charleston and DeMoss escaped the field and were arrested and jailed. The two players were released after posting bail and immediately left town to play winter baseball in Cuba.[26] Charleston was also temporarily dismissed from the ABCs and sent to play for the Lincoln Giants in New York until the controversy died down. He returned to the team in June 1916.[27]

During another incident that occurred in Cuba in the mid-1920s, Charleston fought with Cuban soldiers during a Cuban League game against Havana. He was arrested and fined for his role in the fighting, but was released from custody and returned to the field to play the following day.[28][29] James "Cool Papa" Bell related a story to baseball historian John Holway of another confrontation involving Charleston. Bell told Holway that around 1935 Charleston tore off the hood of a white-robed Ku Klux Klansman during a trip to Florida.[30]

In spite of the controversy surrounding some of his behavior, Charleston contributed to the success of the Indianapolis ABCs. In 1916 he was a member of the team when it beat the Chicago American Giants to claim what the game's promoters called "The Championship of Colored Baseball." (The first Negro League World Series was not played until October 1924.) Charleston left the ABCs at end of the 1918 season to attend the Colored Officer Training Program during World War I, but he served less than two months before the armistice was signed to end the war and he was discharged. When Charleston returned to Indiana in 1919, the owner of the ABCs did not field a team, so he joined the Chicago American Giants.[31]

Negro league player, 1920–1941

[edit]

When the Negro National League was established in 1920, Charleston returned to Indianapolis to play for the ABCs, playing center field for the team in the League's inaugural doubleheader on May 20, 1920, at Indianapolis. The ABCs beat the Giants 4–2 and 11–4.[32] Charleston remained with the ABCs until 1921, then signed with the Saint Louis Giants, who paid him $400 per month, the league's highest salary.[33] Charleston's most productive season was with the Saint Louis Giants in 1921, when he hit fifteen home runs, twelve triples, seventeen doubles, and stole thirty-one bases over sixty games.[34] Charleston's batting average that year was .434; he was also the league's leader in doubles, triples, and home runs.[15]

When the Giants folded at the end of the 1921 season due to financial difficulties, Charleston returned to the ABCs and stayed until 1924, when he became a player-manager of the Harrisburg Giants in Pennsylvania. Charleston continued his career with the Harrisburg team until 1927. After it disbanded, Charleston played for the Hillsdale Club, a team near Philadelphia, for two seasons (1928 and 1929) and spent the next two seasons (1930 and 1931) with the Homestead Grays. As Charleston aged, he shifted from center field to first base during his final years playing for the Giants and two years with the Grays.[34] Charleston also played nine seasons of winter baseball on teams in Cuba. His batting average for the nine seasons was .361.[19][35] A countrywide fan poll taken after the 1925 Eastern Colored League season for an "All-Eastern Team" gave Charleston the most votes, mostly placing him in center field, but he also received votes for left and right field, and as a manager.[36]

In 1932 Charleston became player-manager of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, whose roster included future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and Judy Johnson, in addition to teammates Ted Page, Jud Wilson, Jimmie Crutchfield, and Double Duty Radcliffe. (Cool Papa Bell joined the Crawfords in 1933.)[37] The Negro National League was revived in 1933 and the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays became its leading teams in the 1930s. The two teams competed for more than a dozen Negro League championships and had several future Hall of Famers on their rosters, including Charleston.[38]

Between 1932 and 1936, while Charleston was player-manager of the Crawfords, the team was considered the best in professional baseball. In 1932 the Crawfords played as an independent team and went 99–36, with Charleston batting .363. That year Charleston received the most votes (43,000) from fans and played first base in the first East-West All-Star Game on September 10, 1933. The game was held at Chicago's Comiskey Park in front of a crowd of 20,000 a few weeks after the first Major League Baseball All-Star Game. Charleston was also a first baseman in the 1934 and 1935 Negro League All-Star Games.[39] For the 1935–36 season, when the Crawfords were part of the Negro National League, the team's overall record was 36–24; Charleston's batting average was .304. Charleston was also a member of the Crawford team that won the 1935 Negro National Team pennant. The 1935 Crawfords team is considered the best in Negro League history.[40]

Charleston's career as a professional ballplayer was nearing its end when the Pittsburgh Crawfords was dissolved in 1939 and acquired by new owners. Charleston moved with the team to Toledo, Ohio, but it failed to attract enough fan support and relocated to Indianapolis in 1940. As it did in Ohio, the Indianapolis Crawfords failed to develop a fan base to sustain the team. Charleston retired as a professional player in 1941.[15][41] From 1942 to 1944, he played for the integrated semipro Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot team in the city's industrial league, garnering league player of the week honors in June 1943.[42] In 1945 at the age of 49, Charleston briefly came out of retirement and made appearances in both games of a doubleheader while managing the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers as a pinch hitter and defensive replacement at first base.[43]

Team manager and scout, 1941–1954

[edit]During the winter of 1940–41, Charleston returned to Pennsylvania to become manager of the Philadelphia Stars. The Stars finished the season with a 15–46 record and he was dismissed following the season.[42] In 1944, he returned to the Stars as a first base coach. In 1945 Branch Rickey hired Charleston as manager of the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers in the United States League, but the team was short-lived. Its main purpose was to scout talented black players for the first integrated Major League Baseball teams. When this goal was met, the Brown Dodgers disbanded.[44] Although Charleston was not involved in Jackie Robinson's recruitment, he recruited others, including Roy Campanella.[29]

In 1946 Charleston returned to managing the Philadelphia Stars for five seasons, eventually retiring at the end of 1950.[45]

The integration of Major League Baseball teams in the late 1940s marked the decline and eventual end of the Negro leagues.[46] In 1954 Charleston briefly came out of retirement to manage the Indianapolis Clowns, a barnstorming team that usually played on the road. The Clowns captured the Negro American League pennant in 1954 before Charleston returned to Philadelphia, shortly before his death that fall.[47]

Umpiring

[edit]In addition to serving as a manager and scout, Charleston umpired for the Negro National League beginning in 1946. In 1947, he worked an NNL-NAL all star game at the Polo Grounds.[42]

Death and legacy

[edit]“I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around and have yet to see anyone greater than Charleston.”

—Honus Wagner on Charleston, as quoted on his headstone.[48]

In early October 1954, Charleston fell ill due to a heart attack or stroke. He was admitted to a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, hospital, and died on October 5, 1954, at the age of 57. Charleston's remains are buried at Floral Park Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana.[49]

A renowned player of his era, Charleston was recognized for his athletic skills as a powerful, hard-hitting slugger, his speed and aggressiveness as a base runner, and as a top outfielder. Observers often compared his play to elite contemporaries such as Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Babe Ruth.[50][51] Charleston ranks among Negro league baseball's top five players in home runs and batting average, and its leader in stolen bases.[52]

While The Sporting News list of the 100 greatest baseball players, published in 1998, ranked Charleston only sixty-seventh, only four other black ballplayers who played all or most of their careers in pre-1947 Negro leagues placed higher on the list: Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell.[53] In 1999 Charleston was also nominated as a finalist for Major League Baseball's All-20th Century Team.[29]

Charleston's reputation has grown considerably in recent decades. Baseball writer Bill James, author of The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (2001), reported that Charleston "did everything exceptionally well" and ranked him as the fourth-best player of all-time behind Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Willie Mays.[54] Other baseball observers now consider Charleston as not just the greatest all-around Negro league ballplayer[55] but possibly the greatest baseball player ever.[56][57]

In addition, Charleston's teammates and competitors such as Juanelo Mirabal, Buck O'Neil, and Turkey Stearnes, extol his greatness.[51][19][58] “Oscar Charleston was Willie Mays before there was a Willie Mays,” said “Double Duty” Radcliffe shortly before his death in 2005, “except that he was a better base runner, a better center fielder and a better hitter.”[57]

Hall of Fame manager John McGraw, whose career spanned forty years, once said, “If Oscar Charleston isn’t the greatest baseball player in the world, then I’m no judge of baseball talent.”[57] Renowned sportswriter Grantland Rice wrote a column on Charleston titled “No Greater Ball Player” in which he proclaimed: “It’s impossible for anybody to be a better ballplayer than Oscar Charleston.”[57]

Honors and awards

[edit]- Charleston was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976.[59]

- He was inducted into the Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame, Class of 1981.[60]

- The Indianapolis chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research is named the Oscar Charleston Chapter.[19]

- Oscar Charleston Park on East 30th Street in Indianapolis is named in the ballplayer's honor.[19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "MLB officially designates the Negro Leagues as 'Major League'". MLB.com. December 16, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "A.B.C.'s Take Three From The Sprudels". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana: 10, column 6. May 19, 1915. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Oscar Charleston: Teams Played For". Baseball Reference. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ "Hilldale Team Wins" (PDF). The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 12. August 6, 1919.

- ^ "Harrisburg Takes Two From Chester Team". Chester Times. Chester, Pennsylvania: 8, column 1. July 28, 1924. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Oscar Charleston Manager Page". seamheads.com. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "All Time Negro League Managers" (PDF). Center for Negro League Baseball Research. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ John Holway (1988). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books. p. 114. ISBN 0-88736-094-7.

- ^ a b c The statistics on the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum's website as of March 6, 2018, are based on research that the Negro Leagues Researchers and Authors Group conducted for the years 1920 to 1948. See "Oscar Charleston". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 57.

- ^ Strecker, p. 35.

- ^ "MLB Triple Crown Winners". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for On-Base Plus Slugging". Baseball-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Holway, p. 100. See also: James A. Riley (1994). The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll and Graf. p. 165. ISBN 0-7867-0065-3.

- ^ a b c d "Oscar Charleston". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Holway, p. 100. See also: Geri Strecker (Fall 2012). "Indianapolis's Other Oscar: Baseball Great Oscar Charleston". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 24 (3). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 31 and 33.

- ^ Strecker, p. 36.

- ^ Riley, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e "Retro Indy: Oscar Charleston". The Indianapolis Star. October 14, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ Bill James (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- ^ "Oscar Charleston: Register Batting". Baseball Reference. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Some references provide statistics based on a different time periods. For example, in his book, Shades of Glory (2006), Lawrence D. Hogan lists Charleston's career batting average for Negro league play between 1920 and 1941 was .348, with a slugging average of .576. See Lawrence D. Hogan (2006). Shades of Glory. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 385. ISBN 9781426200335. Baseball historian John Holway reported in his book, Blackball Stars (1988), that between 1915 and 1936 Charleston's batting average against white major leaguers was .318 and included eleven home runs in fifty-three games. See Holway, p. 124.

- ^ Riley, p. 326.

- ^ Holway, p. 100. See also: Wilma L. Moore (Fall 2012). "Everyday People: Sports Champions and History Makers". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 24 (3). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 27.

- ^ Holway, pp. 99 and 106; James, p. 193.

- ^ Riley, p. 165; Hogan, p. 134.

- ^ Geri Strecker and Christopher Baas (Fall 2011). "Batter Up: Professional Black Baseball at Indianapolis Ballparks". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 23 (4). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 28–29.

- ^ James, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Paul Dickson (July 20, 2014). "The Importance of Oscar Charleston". The National Pastime Museum. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ James, p. 165; Holway, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Hogan, pp. 124, 175–78; Holway, p. 104; Strecker, p. 34.

- ^ Strecker and Baas, p. 31; James, p. 166–67.

- ^ Strecker, p. 35. See also: Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, ed. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- ^ a b Strecker, pp. 35–36 and 38.

- ^ Riley, pp. 166 and 629; Holway, p. 105.

- ^ Wilson, W. Rollo (October 3, 1925). "Fans of Country Select Mythical All Eastern Team". Pittsburgh Courier. p. 14.

- ^ Strecker and Baas, p. 31; Strecker, pp. 35–36, and 38.

- ^ Hogan, p. 270.

- ^ Hogan, p. 289; Holway, p. 114; Strecker, p. 38.

- ^ Hogan, p. 289; Riley, pp. 166 and 629; Holway, p. 105.

- ^ Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 59.

- ^ a b c "Charleston Chronology". Oscar Charleston: Life and Legend. 2018-11-23. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ^ "Brown Dodgers Tumble Twice, Lose Ground". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1945-06-18. p. 12. Retrieved 2022-08-01 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ James, p. 173; Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 59.

- ^ Holway, p. 119–20; Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 59; Strecker, p. 38.

- ^ James, p. 168; Holway, p. 119–20.

- ^ Strecker and Baas, p. 32; Gugin and St. Clair, eds., p. 59.

- ^ Cooper, Breanna (2024-05-29). "70 years after his death, Indy's Oscar Charleston will be recognized by Major League Baseball". Neighborhoods. Mirror Indy. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ Strecker, p. 39; Holway, p. 120.

- ^ Strecker, p. 31

- ^ a b James (2001), p.189.

- ^ Ken Mandel. "Five-tool player Charleston considered best all-around player in Negro Leagues". Major League Baseball. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ James, pp. 358–59.

- ^ James, pp. 189, 192–93, and 358.

- ^ wagner, james (15 June 2021). "Baseball Reference Adds Negro Leagues Statistics, Rewriting Its Record Book". The New York Times.

- ^ Bradford Doolittle (February 2, 2022). "What if Oscar Charleston is the best baseball player of all time -- and why it's so important to try to find out". espn.com. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Importance of Oscar Charleston". thenationalpastimemuseum.com. July 5, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ Holway, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Moore, p. 27.

- ^ "Oscar Charleston". Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

References

[edit]- "A.B.C.s Take Three From The Sprudels". The Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana: 10, column 6. May 19, 1915. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- Dickson, Paul (July 20, 2014). "The Importance of Oscar Charleston". The National Pastime Museum. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- Linda C. Gugin; James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

- "Harrisburg Takes Two From Chester Team". Chester Times. Chester, PA: 8, column 1. July 28, 1924. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- "Hilldale Team Wins" (PDF). The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 12. August 6, 1919.

- Hogan, Lawrence D. (2006). Shades of Glory. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 9781426200335.

- Holway, John (1988). Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books. pp. 96–124. ISBN 0-88736-094-7.

- James, Bill (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- Mandel, Ken. "Five-tool player Charleston considered best all-around player in Negro Leagues". Major League Baseball. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- Moore, Wilma L. (Fall 2012). "Everyday People: Sports Champions and History Makers". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 24 (4). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 26–29.

- "Oscar Charleston". Baseball Reference. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Oscar Charleston". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- "Oscar Charleston". Indiana Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "Oscar Charleston". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "Retro Indy: Oscar Charleston". The Indianapolis Star. October 14, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- Riley, James A. (1994). The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll and Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0065-3.

- Strecker, Geri (Fall 2012). "Indianapolis's Other Oscar: Baseball Great Oscar Charleston". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 24 (3). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 30–39.

- Strecker, Geri, and Christopher Baas (Fall 2011). "Batter Up: Professional Black Baseball at Indianapolis Ballparks". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 23 (4). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 26–33.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB, or Baseball Reference and Baseball-Reference Black Baseball stats and Seamheads

- Oscar Charleston managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Oscar Charleston at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Oscar Charleston at Negro League Players Association

- Oscar Charleston at Find a Grave

- 1896 births

- 1954 deaths

- African-American baseball coaches

- African-American baseball managers

- Baseball players from Indianapolis

- Chicago American Giants players

- Harrisburg Giants players

- Homestead Grays players

- Indianapolis ABCs players

- Indianapolis Clowns players

- Leopardos de Santa Clara players

- New York Lincoln Stars players

- Military personnel from Indiana

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Negro league baseball managers

- Negro league hitting Triple Crown winners

- St. Louis Giants players

- Toledo Crawfords players

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- United States Army soldiers

- American expatriate baseball players in Cuba

- 20th-century African-American sportsmen

- Philadelphia Stars players

- Hilldale Club players